Using Manga to Learn Writing Technique

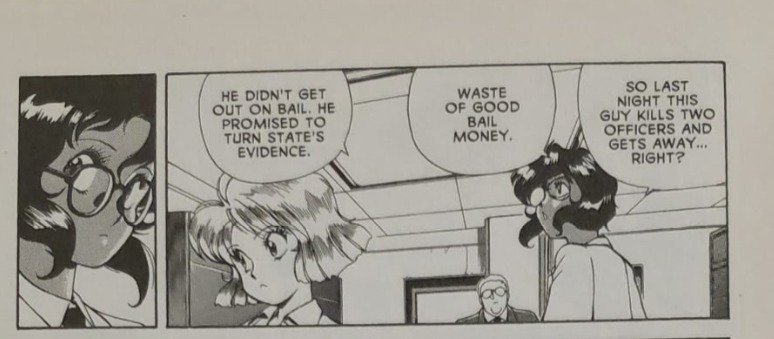

I was reading a manga when these two panels gave me pause, made me pensive, and a concept began gestating in my mind. I won’t bury the lead¹, here are the panels. (Read right to left.)

Notice the panel on the left, which I think could be called a “reaction shot.” What’s the purpose of this panel, do you think?

Even if you can’t put it into words, you probably know intuitively that the character has noticed something. You probably don’t know the specific emotion she’s feeling, but there’s a sense that she’s either been taken by surprise, or her curiosity has been piqued, or something in that vein.

Your next impulse is probably not to begin wondering how you can adapt that to writing, but I welcome you into my obsessed mind. We serve Community Coffee here, the Louisiana brand. Dark roast only, sorry to those of you looking for hints of nut and citrus.

The truth is that a lot of people do attempt to adapt this kind of thing into writing. It usually looks like this:

”So,” Rally Vincent said, “last night this guy kills two officers and gets away, right? Waste of good bail money.”

“He didn’t get out on bail,” said the perp’s lawyer, Phillip Jones. “He promised to turn state’s evidence.”

Rally looked at him. “Dodge was running half the coke in Chicago, a big-time middle-man.”

“But when they pulled him in he was clean, not a grain on him.”

This actually ends up working fine here, and for the same reasons: You’ve directed attention to Rally performing what is otherwise a mundane action, but because you’ve specifically described this, the reader becomes attentive. “Alright,” he says, “this bit of information has apparently captured the main character’s interest. Why is that? It must be for an interesting reason. Something must be going on that makes this whole thing more surprising or intriguing than it may at first appear. Because the character is taking such distinct note, I will as well.”

Not in so many words.

If we look at what makes it work in this instance, there are two primary reasons:

1. First, it opens a new paragraph. Mirroring the unique, somewhat small panel that focuses only on Rally Vincent’s expression, this sentence is short, unadorned, and sits alone with a paragraph indent in front of it and a period behind it.

2. Secondly, there is no other sentence like it theretofore. Every preceding line has some basic information (“perp’s lawyer”), an attribution (“Rally Vincent said,”) and dialogue. Only on this line do we get an action, which sets it apart twofold.

What I really wanted to focus on in this essay is why this kind of thing tends to not work. It just so happened that the example I wrote out above, which was meant to be an example of what not to do, ended up reading just fine and conveying the information exactly as intended. The reader reads, “Rally looked at him,” and we immediately get the impression that she has taken notice of something. Again, we don’t fully know what it is she’s thinking, but her attention captures ours.

This might have ended the article, but if we look at the two reasons above for why it works, we can reverse-engineer it to ascertain why it might not work—and it is my contention here that novice writers fail to make it work more often than they succeed.

So first of all, it’s at the beginning of the paragraph, and a full, simple sentence that ends in a period. If this had been written like this:

”Rally looked at him and said, “Dodge was running half the coke in Chicago, a big-time middle-man.”

Then it wouldn’t have had the same impact, because the sentence structure would not have drawn your attention to the action; however, I think most writers would intuit this and not make the mistake. It’s common to use a simple sentence to emphasize its importance.

So that’s one failed reverse engineering. Let’s take a look at the second and see if it provides any insight. It states that the uniqueness of the sentence—a small, otherwise mundane action by the main character—is what gives it its power. Naturally, this is true for almost anything, even exclamation points. I once read a Louis L’Amour book that had an exclamation point some 70,000 words into the story and it was like a splash of ice-water on the face!

Still, if doing a mundane action to convey a character’s emotion works so well when we do it just once, surely it’ll work even better if we use it a lot. After all, most artists don’t paint only one part of the canvas, they paint nearly the whole thing! Let’s give it a shot!

Rally Vincent looked around. ”So,” she said, “last night this guy kills two officers and gets away, right? Waste of good bail money.” Her tone was wry.

“He didn’t get out on bail,” said the perp’s lawyer, Phillip Jones. He shook his head. “He promised to turn state’s evidence.”

Rally looked at him. “Dodge was running half the coke in Chicago, a big-time middle-man.”

Mr. Jones’ gaze was steady. “But when they pulled him in he was clean, not a grain on him.”

Now we have an instance where we stop seeing this last simple action as a unique, important thing. Instead, it’s just one of numerous physical asides, set apart only by its place on a new paragraph, though that, too, is now mimicked by the following paragraph, thereby utterly destroying any significance it might have reserved via its uniqueness.

I think this is truly the crux of the issue with newer writers, and even intermediates. In our efforts to present a visual spectacle, we forget that we are acting within a written medium, which is a medium with its own strengths and weaknesses, its own techniques and requirements for effectiveness. In a comic, almost every panel can have a facial expression because these are usually character-focused stories in a visual medium; however, even in this medium, not every other panel is a reaction shot of a character’s face, which would be the equivalent of what I did above.

There are more techniques we can take from manga, though. Let’s have a look at the next few panels:

She was really looking for something that could be injected. Oh, a lead? That’s too bad.

Notice what Minnie-May, the blonde chick, is doing. In the three lower panels she is shown noticing something, as demonstrated both by per expression and the three “action lines” framing a quarter of her jaw; she’s shown putting her hand against the wall in the second panel, and in the final panel of the three she’s in the background, facing away from the other two, apparently engrossed in examining something. The rest of the page (not shown here) has her asking Rally to come see something she found and the plot thickens from there.

This is not something that a book can mimic, because it’s not a visual medium. Comics, on the other hand, can have two plots going simultaneously, one in words and the other in pictures. I doubt it’s something that most writers have thought to try, which is fortunate as it’s impossible to replicate in prose fiction.

Don’t despair, though, because there is something similar to it that we can do, and that is by saying two things at once. Consider the following:

Mr. Johnson had Sarah figured out. The first thing she did when she got into work, usually only a few short minutes before he did himself, was make a cup of coffee and set it on his desk. Then she’d go to the lavatory and try to finish her makeup because she always rushed out of the house with her face half-done. If she didn’t get into work before him, then instead of a steaming mug of java, he’d instead be greeted by a flashing message-light on the reception telephone, alerting him to a harried and apologetic voice-message.

The door opened and Mr. Johnson stepped into the air conditioned lobby. It was going to be a busy day. Three new clients and not a single one wanted a prepared package. Sarah could whip up the plans at a good clip once he’d worked them out with the client, but even the best secretary only had two hands. She wouldn’t like it, but Mr. Johnson was probably going to have to hire another receptionist. . . just temporarily, he’d explain. Maybe that’d lower her hackles.

As he passed the reception area toward his office he glanced at the telephone sitting on the reception desk. The message light was off. It seemed he wouldn’t be able to put off telling her for much longer, then. At least he’d have a drink waiting as a consolation.

Entering his office, he saw the paper cup with the plastic sipping lid.

There was no steam coming from the spout.

It was a routine for him to test the coffee first, in case Sarah asked if it was good, but even if it hadn’t been his routine, he would have taken up the cup anyway. He tipped it gingerly, testing the liquid for heat. When a drop touched his tongue he jerked. It was cold!

Frowning, he turned again and went back out the door and headed briskly for the women’s restroom.

What I’ve done here is prime the reader at the beginning with the information about Sarah’s habit of either getting into work and buying her boss coffee, or if she wasn’t going to be in until after him, she’d call and apologize for being late. I ensure that this is the very first thing the reader knows, and it’s described specifically and clearly.

Now, what happens next is that I start describing Mr. Johnson’s normal movements, his concerns for the day, and how it might affect Sarah. And this is important: Potential contention has arisen by Mr. Johnson’s considering of hiring another secretary. It’s obvious by the language I use that Sarah would take exception to this.

I’ve now primed the audience with a second piece of interest.

Now I have him see that the message light is off—the audience automatically begins piecing together the meaning of this. “What was it he said? If she came in after him she’d have a message waiting? So she must already be there.” The reader is engaged in this way. He’s sort of solving a puzzle.

Then I reference again that he will need to tell her about hiring a new employee. The audience is perhaps intrigued by this idea. Oh, I wonder exactly how she’ll react? Maybe there will be an interesting scene of the two employees (presumably both women) getting along, or not liking one another or something?

Then we get into the office, and there’s the cup. So we know she’s there. Only now I state that there’s no steam coming from the cup, and I write this on its own paragraph. The reader, if not fully attentive, should have some sense that something is amiss or at least being given focus. With the line “he would have taken up the cup anyway,” the reader’s internal alarms of an issue might be going off further, and finally when the drink is cold, if the reader is astute, he may recognize that this means she has been there for a good while, long enough for a piping hot cup of coffee to cool, yet she was still in the bathroom?

I’ve, in this way, created two concurrent stories—one of Sarah’s habits, little clues that the reader can put together—and another of the uptick in business calling for the requirement of a second secretary. Incidentally, this could be three concurrent story-lines if the uptick in business is itself an important element of the story, and in fact, whatever is happening to Sarah in the lavatory, or wherever she is, could be considered a fourth concurrent story-line.

When first read, most of this is instinctive, and you don’t actively try to understand it in this way, you simply do, and so my break-down might sound reaching, maybe even absurd, but go back and read it again with these things in mind. Notice how the sentences and ideas tumble upon one another, paragraph upon paragraph as you go, and perhaps you’ll see what I see. Maybe it’ll even be fascinating.

I make no claim to have written something fantastic, only something that demonstrates a concept, however in/adequately.

Wrap Up

So that’s all I’ve got. I hope someone found this useful.