The Line Between Fun and Quality - An Opinion Piece

There isn’t one.

A thank-you to my girlfriend for the lovely reproduction of the Studio Ghibli logo, which I’ve put here solely to make a connection to the offhand remark in the article description, despite the fact that it is never once mentioned in this article proper. I told her to make it look “crappy,” but she can’t follow instructions on the best of days, so we get this splendid rendition. “Simple” doesn’t mean “bad,” Kitten.

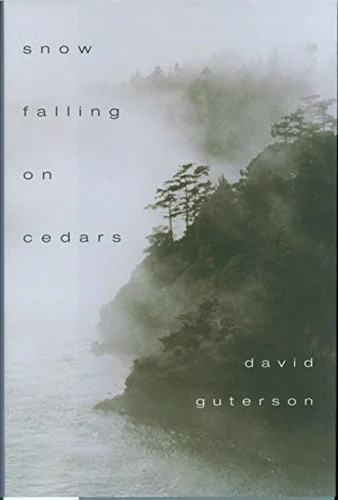

I. Snow Falling on Cedars

Perhaps you’ve engaged with someone expressing the oft-repeated and utterly false notion that “art,” “skill” and “entertainment” are somehow unrelated things. Specifically, the sentiment is expressed thusly, or in any permutation hereof:

Dude, who cares that it’s not good? that it’s hackneyed, uninspired and dull? Lighten up and have fun! Not everything needs to be Schindler’s List or Snow Falling on Cedars.

Notwithstanding the awful implication that all art is dour, dark, dreary, tenebrous, recondite or pretentious, and forgetting presently the question of the likelihood that someone who made the above statement would even know of the book Snow Falling on Cedars by David Guterson, we have plenty of idiocy at which to be annoyed with the simple suggestion here that if something is art then it is excluded from being entertaining or easily understood.

I admit it, I don’t know anything about this book either. I skimmed though. It’s five pages before a line of dialogue is spoken, and even at this point you don’t really know what’s going on despite all the description and the plain establishment that this is transpiring in a court room. Guterson takes subtlety and drags it, nails scraping, into stupefying tedium.

There is a saying related to education: “If you cannot explain it so that it’s easily understood, then you yourself don’t sufficiently understand it.”

I don’t think that’s 100% true, but I do believe that there is enough truth therein that I can draw the comparison: If your art can only be artful by recondity¹, then that is a limitation of skill (or desire) and not a natural consequence of artfulness.

II. I’ve Stated My Case. Now what?

Perhaps as a consequence of improving as a writer, I’ve had occasion to pause and think, “Alright, so I’ve stated my case. I’ve expressed my opinion and backed it with a little bit of what I consider to be logical assertions, but what do I do now?”

Should I end the essay there, short and sweet, or should I carry on? If the latter, then what’s next? What do I want to accomplish, here?

As I’ve concluded in a previous article (link needed), if you are making an argument that is largely logical, an argument that cannot necessarily be proved via the scientific method, then your best tools are analogies, thought experiments, and, in particular, examples. If you say, “A movie can be artistic, or meaningful, and also entertaining,” then it would behoove you to give examples of movies that do this.

When I think of movies that are full of artistry, I think of Jurassic Park, Deepwater Horizon, and the Village. (Yeah, The Freakin’ Village, don’t @ me.)

It’s a typical phenomenon that novel writers, when giving examples of quality writing, use movies as examples. It’s tempting to assume that this is because we are not well-read enough to use an actual novel to make our point, but I have approaching an hundred books on my shelf, and dozens more I’ve read that are not on my shelves, so a lack of data from which to draw can hardly be the reason I’ve impulsively made a list of movies in the previous paragraph. I think it’s because movies are bite-sized books. Bite-sized stories, I mean. You can get a full, wrapped-up experience in an hour and a half or two hours, rather than the eight-plus hours required for a 300-page book. Moreover, while books can leave deep impressions on us, those impressions are oftentimes complex and difficult to express in simple terms. I also think we can find it difficult to parse out what made a book good because after five hours of reading, you’re kind of wrapped up in the world in a way that can dim the visibility of the prose itself. Themselves. The prose themselves? I don’t understand this word.²

The point is that you’re left with the story and the impression it left on you, rather than an appreciation for the technical skill that went into it. . . which I think is what most authors would want. For their stories to be so engaging that the words disappear and there’s only the characters and events and world.

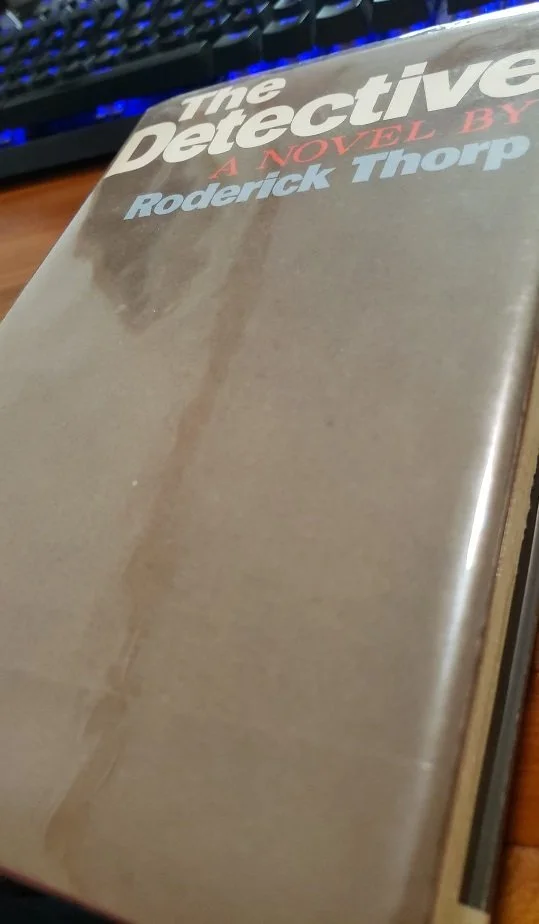

Anyway, now that I’m done fussing over particulars, I’d like to give an example of a book that I consider to be both entertaining and “artsy” in that kind of nebulous, intellectual fashion: The Detective, by Roderick Thorp.

This one.

This is a book that is so dense in its way of writing, yet still so interesting, that I would finish each chapter exhausted, but each day I’d find myself thinking about the book, eager to return to it. It explores ideas of (spoilers) marriage, divorce, love, faithfulness, crime, war, addiction, corruption and even subtle interpersonal interaction. The book is so insightful as it regards how people interact, constantly making subtle implications and suggestions and hints, that I’ve read the book twice and as I write this I’m already considering a third read to take notes.

O.K., I’ve built it up, here’s an excerpt that I will now personally hand-copy over. For context, the main character is Joseph Leland, and he’s just gotten into a cab with his "usual driver”:

He put on his topcoat and started out. There was nothing he could do now. He began to sift the things that Florence had told him.

The newspaper belonged to the cabdriver.. . . The Investigation was led by Detective Lieutenant Joseph Leland, at the time the youngest man

to ever hold that high rank in the Port Smith police department. A career cop who had distinguished

himself as a patrolman before the war, Leland had come back from Europe with a chestful of

medals, including the Distinguished Flying Cross, collected for shooting down (Turn to p. 5)Leland turned.

LEIKMAN SLAYING (Story begins on p. 1)

21 Nazi planes. Now a private detective upstate, Leland is credited with uncovering singlehandedly

the shreds of evidence that revealed the whereabouts of Leikman’s killer. . .

Leland closed the newspaper, glanced at the headline, WHERE IS MARY SHOFTEL? and the newly discovered fuzzy photograph of the seven-year-old beneath, and returned the newspaper to the front seat.

“Had enough, hah?” the driver said. “I could have made a dollar on you. When we saw you coming down the hill, one of the fellows said that you’d get a kick out of seeing yourself in the paper. I said you wouldn’t bother to go all the way through the article.”

Leland drew on his cigarette. “You should have taken his money.”

The driver’s name was Everett. “To tell you the truth, I wasn’t too sure myself. I shouldn’t tell you that, should I? How was it? The article—was it accurate?”

“As far as it went. Sure, it was all right.” The cabdrivers in Manitou worked at getting steady customers. Even when he was late, Leland rode with Everett, if Everett was around. The responsibility for keeping faith was the customer’s, and you had to have a reason if you wanted to change drivers. Everett, a moonfaced farmer’s son in his forties, was all right. Leland had talked him into voting Democratic in the last election.

“Do you know anything about that little girl? It’s a hell of a thing. I can’t even talk about it with my wife.”

“Just don’t build up her hopes,” Leland said.

“Yeah? Shoot, I had hopes of my own. She’d better not ask me if I saw you. Did you ever work on a case like it? I guess not, it would be in the paper.”

Leland flicked his ash out the window, then rolled the window up again. “I saw one, before I went into the service. A teen-ager killed a little girl, then hanged himself. The girl was nine. Her parents knew him, or knew that she had been seeing him, I forget now how it went.” He had seen it by accident; he had been downtown when the bodies had come in. He had been told to go downstairs to take a look.

Now he glanced out the window again. They had reached Senapee Street, the center of the shopping district. It was a broad street, practically empty at this hour. The sky was overcast and boxes of trash were piled at the curb for collection. The street looked bleak and once in a while a neon sign was on, making the sky seem darker than it was. The wind came up the side streets from the river, buffeting the taxi.

Everett steered around a trolley car stopped to pick up a single passenger. “I guess those girls are pretty bad off,” he said. “Before they’re killed, I mean. My wife doesn’t understand how a man does it. Physically. Neither can I, for that matter.”

Everett was curious. “The girls are dead or unconscious before the action begins,” Leland said.

“Dead? I don’t understand that at all.”

“It’s called necrophilia,” Leland said. “I don’t understand it either.”

“Everett glanced at the mirror, saw Leland watching, and looked away guiltily. “Hey, what about the Leikman case?” He was trying to be casual. “They’ve always talked about the crazy stuff that went on in that one. What was that about?”

Leland grinned. “You don’t want to know about that,” he said.

Everett stayed quiet. They passed Bonney’s, which had a new enameled-metal front, covering four stories of aged gray stone. More and more of the stores were going for new fronts, but the ornate wooden eaves remained, the overhead wires, and the trolley tracks, to show the age of the town. The cab rocked again in the wind, and the suspended traffic lights swung. Leland blinked; he was still working the sleep out of his body.

Past the Senapee theater and then, down Clark street, the Gem. At the six-way intersection of Senapee, Otis, and Broadway there were three hotels, a restaurant, two coffee shops, two more movie houses, a second-floor ballroom, a new caffe espresso, and three storefront strip clubs. Leland’s office was on the next block, over a furniture store, a loan office, and a law partnership.

“I hope you’re wrong about that little girl,” Everett said.

Leland didn’t answer. There was no question about what Everett was aiming for. Everett made the U-turn over the trolley tracks and braked the taxi smartly before the building entrance. Leland opened the door and handed a dollar over the top of the front seat. Everett didn’t take it right away. He looked troubled. Leland was going to wait him out.

“Listen, how does a fellow do it? I mean, how does he get in a little girl? They aren’t developed or anything.”

“Well, Everett, the one I saw was ripped open, back to front, skin, muscle, cartilage and bone, the same way a butcher dresses a turkey.” Leland pushed the dollar toward him.

Everett took the dollar and tucked it into the breast pocket of his jacket. He looked back at Leland unhappily. “Will I see you tomorrow?”

“I don’t know. I don’t know what I’ll be doing.”

“Listen, I’m sorry. Are you sore at me?”

Leland patted his arm. “No, no. Don’t be silly.” He got out; he couldn’t wait for a response. He hadn’t lied about his plans and he wasn’t angry. As he headed into the building he had to wonder how Everett abided the emotional scramble in which he hoped for Mary Shoftel and at the same time tried to wring a vicarious excitement out of the worst that could happen to her. The question had been phrased in the abstract, which was supposed to make it different, but he had been too nervous to pose as a man on the search for knowledge. Leland had told him that the girls were unconscious or dead and he had known that they were not developed. It did not take much to put them together and see it for the atrocity it was. Everett had not wanted to give up. Leland could not hold his hand like a child’s. If Everett was going to worry about the dollar a day as well, then it would cease to be Leland’s business.

Apologies for the length, but I felt that the full context was required to appreciate the depth of the interaction. It’s a simple thing, but I did not fully comprehend it when first I read the sequence. If you’re accustomed to reading a lot, maybe you fully understood this scene without a second read or slowly reading it to absorb everything. What I find is that it doesn’t directly state almost anything. Even in the exposition where Leland is sort of just telling you what happened, the phrasing is not so direct that it doesn’t leave a little room for you to infer a little.

The cab driver, Everett, is getting a morbid thrill from talking about this dark subject, but he feels guilty about it, so when he presses for information and Leland tells him, he thinks perhaps Leland might be mad at him for pressing on such a vulgar topic. Leland, meanwhile, knew that Everett was uncomfortable despite his insistent interrogation, and therefore didn’t want to tell him the information if he didn’t have to, but Leland wasn’t disturbed by it personally and, in the end, Leland wasn’t going to patronize the man, to mollycoddle him; nor was he going to be concerned if Everett was concerned that he’d lose his customer. Leland was straightforward and honest in the interaction.

Despite being such a simple interaction, the way it’s paced, and the intrigue of the topic—I’m sure most of us found the subject to be at least a little interesting ourselves—combined with the refusal to be overly direct, creates a sequence that is almost a puzzle that the reader is putting together as he goes, which makes for a very satisfying read. There is sequence after sequence of clever writing like this, and all of it is relevant to the story at hand. Meanwhile, this is basically a detective novel, albeit one that veers into a rather upsetting issue of marriage and wartime absence, described in disturbing detail, but I guess that’s what kind of pushes this into that semi-literary style: The willingness to push into unhappy topics that can take up chapters. It’s a story as much about Joseph Leland’s life as it is about the case he’s trying to solve, where a man has apparently flung himself from the roof of a racetrack balcony, or something like that, I don’t know how these racetrack stadiums are built.

The point, in any case, is that a story can be intriguing and entertaining, yet possessed of such skill that it is edifying by the very nature of its quality. I think the Detective, by Roderick Thorp, is one such story.

Another is the Return, by Joe de Mers, one of which I will spare you a lengthy excerpt. I would like to discuss it a bit, though. It’s a book that is the writing equivalent of a director like Steven Spielberg, Wes Anderson, Alfred Hitchcock or Christopher Nolan: In other words, it’s clever, well-paced, suspenseful and has a thorough understanding of what it is and what it’s trying to do. When you watch a movie by a high-quality director, say, Quentin Tarantino, there’s a “feel” the movie has that most films do not, because most films are not made by masters of their craft. The moment you begin to watch a movie by one of the masters, even if you don’t end up liking the movie, you can sense something different: a level of competence and creativity that permeates every shot.

This is how the Return is. Every single sentence is a carefully crafted piece of art, tumbling effortlessly into paragraphs and pages, compelling you to read on. And this is coming from someone who would not likely read that book a second time, mostly for personal reasons, but I was thrilled from start to finish, not just by the mere entertainment of the premise (Jesus Christ appears to have returned to earth and performed miracles; a priest whose faith in the church is wavering investigates) but by the skill and wit. I think that there is something fulfilling and uplifting inherent in sheer competence, something that strikes at the heart of us as emotional beings, a kind of intermingling of intelligence and spirituality that sends our spirits aloft, that impacts us on a level equal to and deeper than the visceral.

So that’s why I think that dumb, poorly crafted, meaningless entertainment is not necessarily to be enjoyed, but that clever, skillfully crafted entertainment, made solely for the sake of entertainment, is. There is nothing wrong with needing quality and skill in one’s mindless entertainment, and there’s nothing wrong with having a critical eye. I believe that while anyone might enjoy a mediocre movie or book, I don’t believe that the level to which it can be enjoyed is as lofty as for that which is excellent, assuming we’re talking about enjoying the media for the sake of the media. If you’re with a group of friends and watching the Room, that’s a different thing altogether.

Well, I think I’ve done my due diligence in ensuring that my article contains more original words than excerpt words. I guess that means I’m done.

Afterword

I thought it would be kind of nifty to put the song I was listening to while writing this article here, so here it is:

Band: Megaton Sword (I’m not making that up, seriously.)

Song: The Giver’s Embrace

Album: Blood Hails Steel - Steel Hails Fire

Genre: Heavy/Power Metal

Link. You’re welcome.