A Review of the Video Game ReCore; or, the Problem With Open-World Games in General

My girlfriend has read and approved this article. She also did all of the original art. You can tell which pieces are hers because they almost certainly involve cats somehow.

I. How It All Began

Right here.

I’m being facetious in the picture caption, but also sincere. Look at that art. You’d have to at least check out a few screenshots of the actual game after seeing it, wouldn’t you? I did, too.

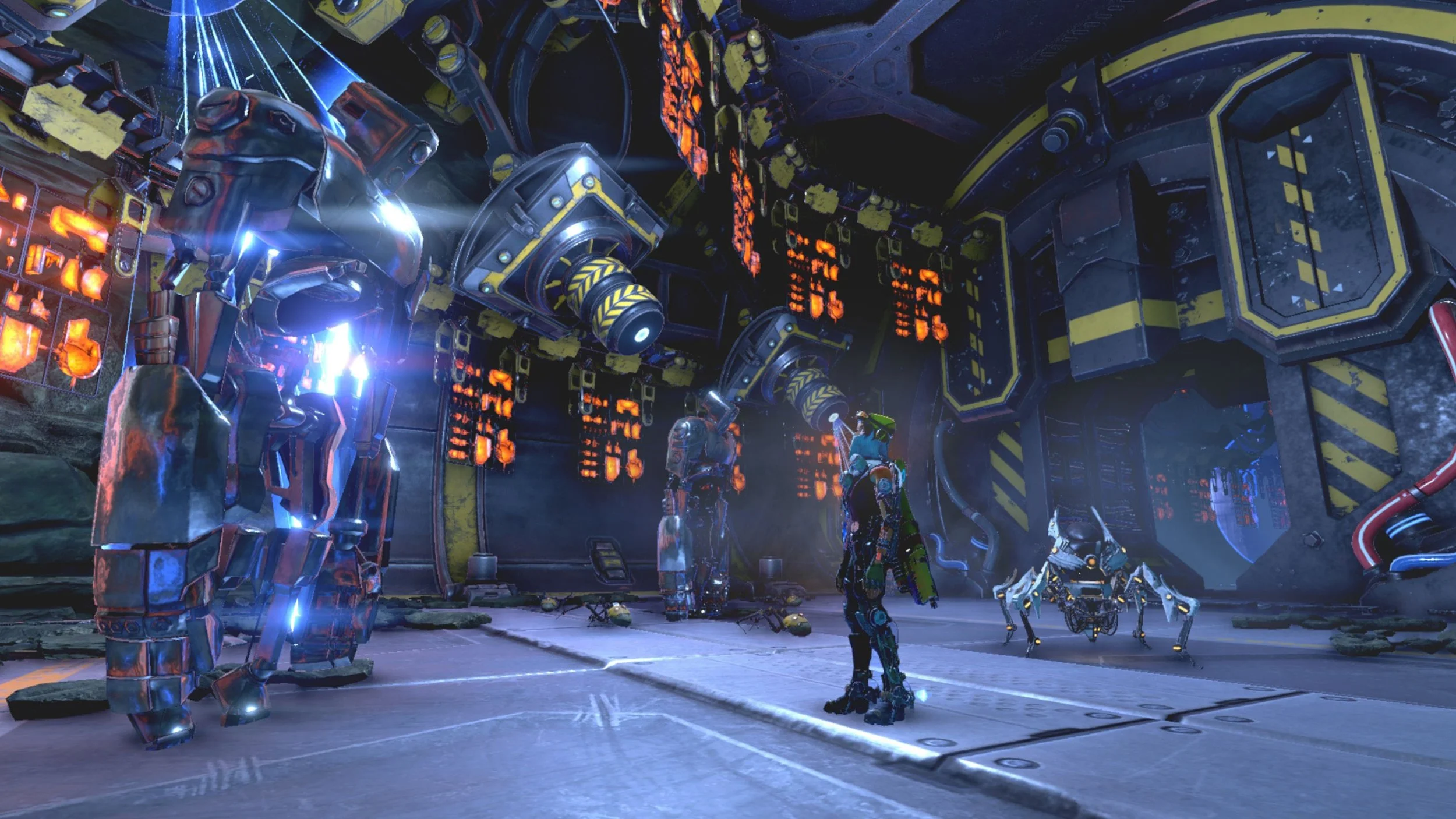

Here’s what that looks like.

Here’s another to whet your whistle.

So you see how I might have been enticed. Might have been, and was, too. I remember thinking, there’s no way that I won’t like it. Even if it’s not perfect, I’m at least going to have a general enjoyment.

There was no way I wouldn’t.

This article is evidence to the contrary. I hadn’t yet written this article at the time, so I guess I blame myself.

You’ve probably heard it a lot. “I wanted to like this game.” We don’t ever explain what that’s supposed to mean. We all intuit what that means, but maybe it’s worth defining our expressions. When I say that I wanted to like it, I’m expressing the amount of good will I had extended toward the game. I liked the art style, I liked most of the mechanics, I liked the presentation of the packaging before putting the game in, the cut-scene that occurred right after putting the game in, and the feel of playing once I was given control. Because I’d never heard of the game before—despite how beautiful the game looked—I felt the natural human desire to root for the underdog, and to be the discoverer of a dirty, errant gemstone: to be the one who worked it free of the soil with both hands, took it home and cut it, polished it and then worked it onto a silver band to display to all of my reluctant and uninterested friends and family.

In other words, if there were any reason to keep playing, I’d find it, and if there weren’t a reason, I’d invent one. I was on a mission to enjoy this game and make it a favorite game for the express purpose of being someone who did, and vaunting to people who would invariably be unimpressed, and then, slighted, retreating inward to speak vile things about how they “don’t get it,” even though I’d had to relinquish all hold on logic, reason and even rationality itself to come to the conclusions about the game that I had come to.

The one thing that got in the way of my mission of self-deluded love for this game was the game itself.

The plan never goes exactly as planned.

II. Mission Statement

In doing some minor research for this article, which involved mostly looking up pictures on the internet to break up the text in much the same way as chapter breaks in novels, I came upon an article about how ReCore Doesn’t Deserve a Definitive Edition.

I admit, it kind of took the wind out of my sails because a good portion of the problems I have with the game are already mentioned in that editorial. Not only does that suggest that other people have said what I want to say, but it’s also common knowledge.

When I started this game I wanted to be one of the Chosen Ones who had the willingness to find and purchase and play this game despite its general invisibility, and thereby have the pleasure and honor of enjoying its underrated glories. Then, when I began to conceive of this article, I wanted to be a dissenting opinion, the one man brave enough to make a stand and report on this game’s failures.

I can be neither of those now, so what will I do?

Obstinately persist in writing the article, of course. Insisting, with stubborn foolhardiness, on creating an exhaustive list of every issue I can think of, consequences be damned!

The consequences, of course, will be a lot of effort and zero reward but be they damned!

That little outburst said, I figure I can thinly veil my redundant effort in the conceptually lofty contrivance that I’m here to make a bigger point, which would encompass not only ReCore but open world games at large.

So let’s do that.

Pictured Above: An embarrassingly meager attempt at salvaging an essay idea.

III. Enumerating the Game’s Problems (of Which There Are Many) Starting With the Excessive Size of These Games in General, and This Game in Particular

In the spirit of incidentally lashing this whole negative review to a more sophisticated point about open-world games, I’m gonna start with the size of the world: It’s way too big, and therefore there’s too much walking around—either aimlessly, or to a destination whose arrival time is needlessly excessive.

It’s taken me some time to develop a sensible opinion on open-world game design, since I’m really a casual gamer who occasionally becomes obsessed with a particular game and then writes thousands-of-word articles on them. I’m a novelist by trade hobby, so I do have some meaningful thoughts about story and dialogue, but from the perspective of game design I have strong ideas but little experience, so whether my ideas are right generally depend on who’s listening.

Having played this game and stopped midway through due to too much running around and performing busywork, and having played Horizon Zero: Dawn (or is it Horizon: Zero Dawn?) and stopped midway through due to too much running around and performing busywork, I’ve become convinced that giant maps, running around, and busywork are three things games can do without.

And boy does this game love running around! The map is huge, relative to your size and movement speed, so you spend a lot of time just wandering about, slowly. I shouldn’t need to play my Nintendo DS between points of interest.

I hope you’re enjoying the view, because it’s all you’ll be seeing for forty hours.

I have no clue what the solution to this is. On the one hand, having the world there is really cool, and at least initially I wanted to run around looking at things. On the other hand, after doing it a couple times you’re no longer enamored with the visuals and it just becomes a time sink. Someone needs to figure this mess out, because fast-travel doesn’t really solve the problem, it just effectively eliminates the open world, so why not have a map from the very beginning with locations that you can click on that immediately teleport you to those locations? It would be the same thing, but without the need to trudge for literal real-life miles through uneventful fields to get to something interesting.

Maybe the solution is just adding a lot of stuff to the map?

Or not.

Ya can’t! Look at this map. Boy, I bet you can’t wait to clear those. I mean engage with them in interesting and meaningful ways.

Who are we kidding? We rarely go to these markers because something of value is there. We go to them because we want them to disappear, which gives us a small dose of dopamine, but not much; for that, you need to go to another marker and complete that one’s redundant task too. This is your fault as much as the developers. You can’t just go to one or two markers to max out your sense of accomplishment. The doper needs to keep doping; likewise, the dealer needs to keep getting paid.

This map is not here to entertain you, but to amuse you. And it’s your fault.

You thought that was a positive thing?

You’re meant to stupidly stare at the screen, jaw slack, mind sluggishly processing, never engaging, only acting on the lizard-brain impulse. It’s hijacked your baser instincts and now you’re checking boxes to the congratulatory jangle of keys. Great work! Now do it again.

The actual game slips in and reengages you so that you thought you were having fun the whole time, but in reality your desire to progress—not in the game, in life—was being manipulated. You thought, subconsciously or physically or somehow, that you were getting somewhere, that you were accomplishing something. Instead of writing that book, learning a skill, drawing that comic or starting that Youtube channel, things that would allow you to create, to pour your spirit into something, you were instead allowing someone else’s creation to leech upon one of your most precious resources: time.

So yeah, busywork isn’t a solution to the dullness; it’s a pacifier for the unambitious, the languid and the complacent.

IV. Lack of Progression

I hope you like this character interaction, because it’s going to be the primary one for 90% of the game.

I also hope you like this phrasing device, because it’s a running gag, now, because the only other option is thinking of something else.

So now I have no choice but to talk about the nature of video games in a pretentious breakdown of concepts that we all intuit but few of us ever actively consider. If I don’t, I’d have to think of another way to write this section, and that would require more effort, effort that sounds far too daunting to expend. I’ll try to make it brief and as interesting as possible.¹

So when you read a book, there are several points of interest. Yes, I’m using books, alright? I’m a novelist.² It’s what I do.

The points of interest in a novel are character and plot progression; but those are only the primary points of interest, the obvious ones. There’s another one. Collectively, it’s writing style, word usage, sentence structure, that kind of thing. In a movie the equivalent would be camera work and lighting and music choice. In a video game it’s mechanics.

Peradventure you’re playing a video game. You have an opening cut-scene, which gets you into the story. You have the beautiful scenery that captures your visual interest. As you move around, shoot, punch or whatever, you are engaging with the feel of the game, the mechanics, and for most games this is the most important part. Now what the game needs to do is give you a reason to use these mechanics. Put you in an arena with some boxes and punching bags and you’ll become bored quickly irrespective of how satisfying the striking mechanics are; likewise, no matter how pretty the words are in a book, if they don’t mean anything or take you anywhere, then your interest will be transient.

O.K., I’m almost ready to get to the main point, but there’s one more thing that video games have that other forms of media don’t, which is the ability to collect things that give you a sense of ownership. More specifically, you can grow levels, gain strength, learn new abilities or spells depending on the type of game, or collect new weapons. The importance of this is that it gives you a sense of progression, something to aim for.

Now that’s the crux here: Progression. All of the things I mentioned—characterization and plot movement and gaining new weapons and access to new locations—it’s all progression, and as a reader, or uh, player, you want to feel like you are progressing.

So what does ReCore give you?

Well, within the first couple hours I had collected three robot companions, gained and lost a human companion, collected four firing modes for my gun, and finally learned that there was nothing else. That’s it.

You gain no more companions. Your companions gain no more abilities. You only have the one weapon throughout the game, which has no more than these four upgrades, all of which are basically just a rock-paper-scissors puzzle. Use one color against a particular enemy color and the like. You don’t gain any new outfits, and leveling up only increases health and gun damage to an imperceptible degree. You can customize your robot companions, but they’re not interesting enough to bother doing so, especially because, in order to collect parts for them, you have to wander around a huge desert for hours, repeatedly doing the same activities.

So there’s no progression in game mechanics, but what about in story?

Well, the story is fairly minimal. It does capture your attention at first, but by time you find a few recordings that give context and greater information on how the whole scenario the main character is in came to be, you realize that you’re basically playing one story and listening, via recordings, another one. You don’t feel particularly connected to what’s going on in the recordings or in the readable documents you find. You’re here in this vast empty nothingness, unable to talk to any of the characters that you hear about.

The one character you meet early on disappears in ten minutes and I never got far enough to determine whether or not he shows up again. There may be more story to the game, but it’s delivered so sparsely that it never gets you to the point that you actually feel anything. I didn’t, anyway. Nor was I compelled to find out.

And characterization? Well, for that you need characters. As I mentioned, the one other you meet disappears quickly. There’s another one of those little robot companion guys who can talk, but he only shows up at teleportation locations and, for some reason, the game creators thought it would be cute to make him speak in squeaky gibberish, even when he’s saying sincere and serious things, so you can’t really get into it even if you want to. Talk about shooting yourself in the foot! If he had spoken in an intelligible language, it could potentially have pushed me to play a bit more, knowing that there could be some interesting interactions.

So there’s a scant story, virtually no characters, very little plot movement and within the first couple of hours you’ve unlocked all of the weapons. Even with the whole game ahead of me, I distinctly felt like there was nothing to do.

Contrast that a game like Contra.

Behold: Snappy Storytelling

Why should Contra, with almost no story at all, virtually no voice acting, no dialogue, a tiny play area, no characters of substance, and a minuscule move pool work so wonderfully? You can’t even move in three dimensions!

Because what it lacks in all of the above it compensates for, dramatically, with pacing: You don’t stop moving, the scenery doesn’t stop changing, new challenges don’t stop coming. You get new music, new stages with entirely new visualizations; new enemies with new attacks—and all of this is tightly packed into a game that can be beaten in an hour. (Though, this being Contra 4, you probably won’t beat it in an hour. You might not beat it at all. Go play it anyway. It’s awesome, if only for the music and visuals.)

ReCore, contrariwise, is huge and expansive and lasts much longer, but that means all of its events are spread much farther apart, so what are you doing between missions? Nothing. I could be more specific, but why bother? The word nothing sums it all up.

The same could be said for most other open-world games, though I give a bit of a pass to Lord of the Rings: Shadow of Mordor for having a relatively small map and probably thousands of voice lines to keep things feeling alive. In fact, unless you go out of your way to find all of the little trinkets and do all the meaningless side missions, the game will run at a solid clip, and you will constantly be learning new moves and facing new challenges.

The bigger your game is, and the less to do that there is crammed in every second, the more you need to compensate for that by making things happen in the spaces between, or at least you have to give the player a reason to think it’ll be worth it.

ReCore never does.

V. Boring, Tedious Challenges

I really hope you like this the first time, because if you don’t then I have bad news.

So the game’s too big, has too little story, too few characters and nothing to collect or upgrade in any interesting way. . . but what about challenges and the like?

Well, challenges generally need a couple things to be fun: First they need to be fun in and of themselves, apropos of nothing else.

There are two primary challenges, which take the form of platforming with your character’s standard move-set of jumping, double-jumping, dashing and air-dashing. Due to decent movement mechanics, this ain’t that bad. Combined with shooting special objects and having rewards at the end that are given based on speed and other requirements, these have the potential to be very fun.

The issue is that there’s just not enough incentive to complete them more than once, or at any higher levels of difficulty. The rewards you get are basic health upgrades and cores (or ReCores? I don’t recall anymore), which are not particularly interesting or apparently useful. You may also need to do the challenges multiple times because the way the platforming is set up, you may not see certain things you need to shoot, or you may not be prepared for how the platforms will move. It’s understandable, you don’t necessarily want it to be achievable on your first attempt, but difficult challenges should be reserved for challenges with meaningful rewards, such as new weapons—of which this game has none—character moments—of which this game has few—and new abilities. The game doesn’t have those either.

The other type of challenge is the tank challenges.

Don’t you give me that oblivious grin. You know exactly what you did. Now come over here and help me set this broken leg.

The tank is a robot companion that you can ride. It’s fast and therefore useful, but the controls are not intuitive, and even when you think you’re going to make a jump, it seems like it always lists one way or another and you get flung in the wrong direction, or stop entirely, or go spinning off of a cliff. Fortunately you can save yourself in the same way Mario can leap from a doomed Yoshi after a jump falls short, but at that point you’ve almost certainly failed the speed challenge so you may as well give up and start over.

Again.

I hate this game.

Because of the awkward control, you rarely feel like you lost fairly, and it’s even more rare that you think, “I’m gonna try again.”

When I found myself pushing through challenges, not caring about getting the lowest possible score, and feeling a relief that was still a mere undertone to a more prominent and persistent annoyance, I decided that it wasn’t worth doing them anymore. Much like the rest of the game, it has some acceptable ideas, but it executed them in a way that makes them feel pointless, and then shrouds the pointless ideas in annoying difficulty, and then when you finally, painstakingly complete them, it slaps you in the face by giving you humdrum rewards.

I promised I would relate my niggles (and larger, more extreme niggles known as naggles) to the state of open-world games as a whole.

I think the connection is obvious, and therefore need not be stated.

So I’m gonna go ahead and state it.

Oh. Hello, again.

I have a day job. I also upload to this website that no one reads, and I’m writing a novel, practicing short stories, and I also spend a lot of valuable time procrastinating. I don’t have any time left to spend on getting invested in a big empty world with big empty “challenges” designed almost exclusively to waste the player’s time.

“They’re just industry standard.”

Oh, so they were created to waste the developers’ time? I’m just saying, the only reason they exist is to “give you something to do,” but isn’t that what the rest of the game is for? Even well-done side-challenges of this nature are usually, at best, boring after the first few. Am I playing because I want to fight robots and see a story unfold, or am I playing to perform small, clunky challenges that test me on skills at a level far beyond what’s required to play the primary game? I have a life, my time is valuable. I was not entertained. You failed. Next.

Open worlds are designed to waste your time long enough for the developers to get another game out, which seems to be a failing strategy since most games are still released with dozens of bugs, so what’s the point? Maybe you could save some time by not including these mind-rotting side-quests and instead just focus on making a concise, entertaining and bug-free primary experience.

I’m sorry, do I sound bitter? I think I sound bitter. It’s gratuitous, I know.

As a side note, I don’t think this is entirely the developers’ fault. If you make the game under 30 hours, people complain that it’s too short.

“I should get more for my money.”

Did you not have fun?

“No, it was great, I just wanted more.”

Sounds like the game was 100% a success, then. Maybe just wait for a sequel.

“Aw, sequels usually suck!”

Yes, that’s been my experience, too. Back to the 60-hour grind it is, then.

VI. Games Aren’t Made for Men With Precious Little Free Time

Most games today are made for people who have an excess of leisure time, or for adults who are trying to check out of the real world. It’s perhaps possible that all of these inane addendums to the gameplay are enthralling to those who are under no pressure of limited time, who are able to play multiple hours a day without fear of neglecting their obligations. To those of us looking for a couple hours of entertainment to cap off an evening or, heavens, a week, these elements provide nothing but tedium that we cannot afford to engage with.

“Then why don’t you just skip those parts of the game?”

Do you skip story prologues? Exactly.

Wait, you do? O.K., well, I don’t. The prologue is part of the story. If the prologue is badly written, I don’t skip it, I stop reading the story. Why should I think that if the prologue (AKA, chapter 0) is written poorly, it’s an anomaly? That was the author’s opportunity to hook me and he blew it. The next author will be happy to pick up the slack.

If a video game is giving me a dozen points of un-/dis-interest, then it must believe that they are worthwhile, and if they think they are worthwhile, and they’re wrong, then why should I think that they were right about the rest of the game?

And you know what? they might be right, the rest of the game might be fantastic, but games shouldn’t be something that you understand as having been developed by a committee, requiring a lot of fluff and squander as a prerequisite. A game, for me, is a complete entity: take the good with the bad, or leave it all behind. You don’t get my good graces, and that’s because I don’t need to provide them; there are a lot of other games vying for my attention, worthy games who have chosen not to squander what precious little downtime I have.

I eat healthy every day to maintain my health, and when I go out to a restaurant I’ll be accursed if I’m going to order a healthy steak. I’m ordering french fries and Molten Chocolate Lava Volcano Cake. Video games are my restaurant of, wait. . . restaurants are my restaurants. Video games are like restaurants, or. . . .

The point is that I’m not going to give a video game any more chance than I feel it deserves at any point, which is my prerogative as a busy customer. These open world games don’t respect my time, and hopefully one day the industry returns to the more carefully curated single-player standard.

Or not. I’m happy to keep playing Sifu.

Polygonal action and not a wasted second. Well, that’s not true. When you die a bunch and restart you have to keep watching your main character enter the area in a cut-scene that’s approximately eight seconds long.

VII. In Conclusion

No need to waste your time on it. I already played it for a few hours and lost interest on your behalf. You’re welcome.

Then again, if you just love task-based gaming, long and uneventful periods of plain traversal, clunky tank controls, repetitive challenges and virtually no meaningful progression, then I’ve got a slew of games just for you.

You thought I was above using this image again? You poor, sorry fool. This is it. This is the payoff of the whole article. It’s over now. Bye.

I give it one out of four Kitty Paws:

Not worth your time.